Sermon: Flesh and bones

Luke 24:36-48

One recent morning, Min-Goo and I were discussing “boundaries.” Min-Goo said, “You remember the priest who came from Myanmar. He invited us to his home for dinner a few times, when we lived in residence on the UBC Campus.” It was almost ten years ago now; Back then, we lived in the residence next to to the Iona ‘castle’ building at Vancouver School of Theology for about three years. Among the students, there were just a few of us who came from different countries. “One time he said to me,” Min-Goo continued, "'Canadians are cold and their heart is like a machine.' I wonder if the boundary you are talking about is what he tried to say at that time.”

When you come to this country as a newcomer, the first thing you learn (or not just learn; you learn that you must learn and understand this and work around it) is “boundaries,” or “personal boundaries.”

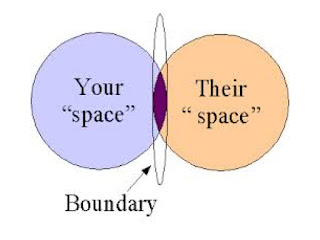

If you come from a collectivist culture, (not individualistic) the concept of personal boundaries is new and confusing. According to Wikipedia, personal boundaries are guidelines, rules or limits that a person creates to identify reasonable, safe and permissible ways for other people to behave towards them and how they will respond when someone passes those limits.

To speak of my own experience, my first impression of Canadians was that most people were kind and compassionate, as long as we knew the boundaries and adopted the rules. To me, personal boundaries are still something foreign and hard to completely follow and be happy about. Building mutual relationships is very hard for many newcomers because they often do not know when and how mutuality start to bloom in the relationship. It often seems that the possibility is dependent upon another person’s willingness to open their heart and let us come into their life. A typical personal boundary may be illustrated like this: Stretch one arm out straight in front of you and turn around to make a full circle.

The circle that is drawn at the edge of your finger is a typical, North-American-style personal boundary. In its positive function, it is helpful. It helps you to know your rights, who you are and what you need. Its main function is related to protection and containment, regulating the incoming and outgoing in the interactions between people. It exists to protect a healthy divide between oneself and the world, oneself and the other. Yet, it is in its nature based on hierarchical understanding, distance, neutrality, and power.

According to my Google search, there are several areas where boundaries apply:

Material boundaries determine whether you give or lend things, such as money, your car, clothes, books, food, or toothbrushes.

Physical boundaries pertain to your personal space, privacy, and body. Do you give a handshake or a hug - to whom and when?

Mental boundaries apply to your thoughts, values, and opinions. Are you easily suggestible? Do you know what you believe, and can you hold onto your opinions?

Emotional boundaries distinguish separating your emotions and responsibility for them from someone else’s. It’s like an imaginary line or force-field that separates you and others. There are sexual boundaries and spiritual boundaries as well.

Many popular self-care and self-help books available in North America, generously use and favour the concept of personal boundaries.

They would tell us that love can’t exist without boundaries.

It is very true, but I wish to invite you to ponder with me why and how we may have become so accustomed to and feel so comfortable with using (or overusing) the concept of boundaries to articulate the model for right relations between people and communities.

I have theological and spiritual concerns regarding our generous use of the concept of boundaries. For example, translate all the descriptions attached to personal boundaries to white privilege or male privilege. A personal boundary makes more sense when you have a privileged status and are a privileged individual, or when the individuals in the relationship are equal. The flip side of the personal boundary is that you have the right to separate yourself from the thoughts and feelings of others and not to engage with them because you have no responsibility for the other’s well-being if you don’t choose to. You have the right to protect yourself from being violated by others, but what happens when your idea of ‘violation’ is being asked to consider any idea that challenges your sense of supremacy?

Boundaries don’t work so well and makes less sense when the oppressed want solidarity, seek mutuality, and ask you to stay with them in their pain and hurt, but your own boundaries exclude acknowledging the pain and hurt you may have caused or benefited from.

Our reference, our ultimate reference is Jesus. Jesus’ Gospel doesn’t have a single chapter that teaches us boundaries.

In its root and foundation, ‘boundaries’ are an ethic that emphasize distance, neutrality, separation, and individualism, an inheritance from white, male, patriarchy.

Keeping healthy boundaries is important for right relations, yet it is not equivalent to a right relationship. For being in right relations or relationship, we need more than healthy boundaries. What is the ‘more’? I believe these are the questions the Gospel teaches us to ask.

In today’s Gospel story, the risen Jesus stands among the disciples, coming from and out of nowhere. The disciples are startled and terrified, thinking that the other is a ghost. Not real. There’s a sense of “This is something wrong.” This presence is unexpected!

The first word that Jesus uses every time he appears to his disciples after Easter is, “Peace”. The disciples are terrified, in fear, looking at this unidentified other who has intruded and is standing in their space, in their boundary, without warning. (That’s Jesus’ first violation of their personal boundary.)

Jesus says to them, “Why are you frightened?” “Look at my hands and my feet; Touch me and see; for a ghost does not have flesh and bones.” He shows them his hands and his feet. (Jesus has rather a loose physical boundary).

Then, here’s my favourite part: This is the revealing moment in which we can sense who Jesus is and what he teaches. Jesus is the authority, the master, the teacher, the God, the divine. We are quite familiar with the stories in which Jesus’ actions accord perfectly with his divine status: He breaks the bread and gives it to people to eat. In the post-Easter story in the Gospel of John, the risen Jesus meets the disciples at the lakeshore, cooks the fish on the pit fire, calls them, and gives them food to eat. In the previous story in the Gospel of Luke, Jesus also reveals himself to the two disciples on the road to Emmaus by breaking the bread and handing it to them. He is the High Priest who performs the sacrament. No story reports how Jesus ate. In today’s Gospel story, Jesus is a hungry person, with real flesh and real bones, real peace and real humor, asking the disciples, “Have you anything here to eat?” (challenging the material boundary).

One commentary says this story reveals “The most unashamed, materialistic nature of Easter”.

Jesus of such power shows without shame his materialistic, physical need and vulnerability, and makes the disciples relate to him by giving him what they have: a piece of broiled fish. The story tells us that Jesus takes it and eats it in the presence of his students, in front of the eyes of his students, watching him until he finishes. I imagine that Jesus eats with care, with respect, slowly, taking his time, unhurried.

Our theology and spirituality are more concerned about person-to-person-touching; The gospel teaches us that we should always be more concerned about one-more-person-to-be-accepted than about our-boundary-to-be-protected. We are, in Christ, willing to stay in the ambiguity and sisterly and brotherly love and solidarity, looking toward mutual relationships - our ears, eyes, minds, hearts open to incoming and outgoing stories - boundaries opening two ways.

Our culture seems to be so addicted to spreading the self-care, self-help lessons of boundary-keeping and maintenance. However, we are also reminded that for Christians, spirituality is more like

- opting to be vulnerable.

- Letting ourselves be taken advantage of

- absorbing pain and suffering

- receiving the gift of inconvenience

- taking risks and being overwhelmed

- growing in relationships of interdependence.

Our ultimate reference of such spirituality is Jesus. Touch and see the Jesus of warm flesh and strong bones, here, lovingly within your boundaries.

Comments

Post a Comment